INDIAN ARMED FORCES CHIEFS ON OUR RELENTLESS AND FOCUSED PUBLISHING EFFORTS

The insightful articles, inspiring narrations and analytical perspectives presented by the Editorial Team, establish an alluring connect with the reader. My compliments and best wishes to SP Guide Publications.

"Over the past 60 years, the growth of SP Guide Publications has mirrored the rising stature of Indian Navy. Its well-researched and informative magazines on Defence and Aerospace sector have served to shape an educated opinion of our military personnel, policy makers and the public alike. I wish SP's Publication team continued success, fair winds and following seas in all future endeavour!"

Since, its inception in 1964, SP Guide Publications has consistently demonstrated commitment to high-quality journalism in the aerospace and defence sectors, earning a well-deserved reputation as Asia's largest media house in this domain. I wish SP Guide Publications continued success in its pursuit of excellence.

- Global Partners Urged to Tap India's Shipbuilding Potential: Rajnath Singh at Samudra Utkarsh

- All about HAMMER Smart Precision Guided Weapon in India — “BEL-Safran Collaboration”

- India, Germany deepen defence ties as High Defence Committee charts ambitious plan

- G20 Summit: A Sign of Global Fracture

- True strategic autonomy will come only when our code is as indigenous as our hardware: Rajnath Singh

- India–Israel Joint Working Group Meeting on defence cooperation to boost technology sharing and co-development

Coastal Security

Maritime Domain Awareness and Security Imperatives

In 1982, the Common Heritage of Mankind concept was stated to relate to “the seabed and ocean floor and subsoil thereof, beyond the limits of national jurisdiction” under Article 136 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea Treaty

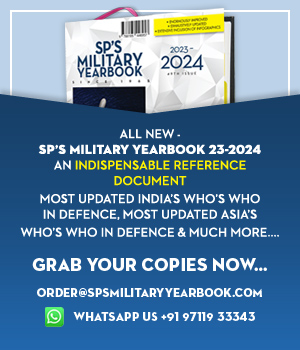

Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) is defined by the International Maritime Organisation as the effective understanding of anything associated with the maritime domain that could impact the security, safety, economy or environment. The maritime domain is defined as all areas and things of, on, under, relating to, adjacent to, or bordering on a sea, ocean, or other navigable waterway, including all maritime-related activities, infrastructure, people, cargo, and vessels and other conveyances. Thus demarcation of sea border of a country remains pretty much complex.

The Indian Navy publication The International Law of the Sea and Indian Maritime Legislation stipulates, “Over the centuries the international law of the sea had come to be based on the basic principle of “freedom of the seas”. Beyond the narrow coastal strip of territorial waters, the seas could be freely used by all nations for fishing and for navigation. Coastal states used to be content with exclusive rights in their narrow belt of territorial waters. The discovery of petroleum and natural gas in the shallow waters of the continental shelf led the US to issue the Truman Proclamation in 1945, which claimed sovereign rights over the resources of the continental shelf adjacent to its coast. Around the same time, coastal states found that the fishing areas near their coasts were being poached by larger and better equipped fishing ships of distant foreign states. Both these developments, combined with the emergence of newly independent states after the decolonisation of Asia and Africa, led to a spate of unilateral claims by the coastal states to extend national jurisdiction over large adjacent sea areas to protect their fishery resources.”

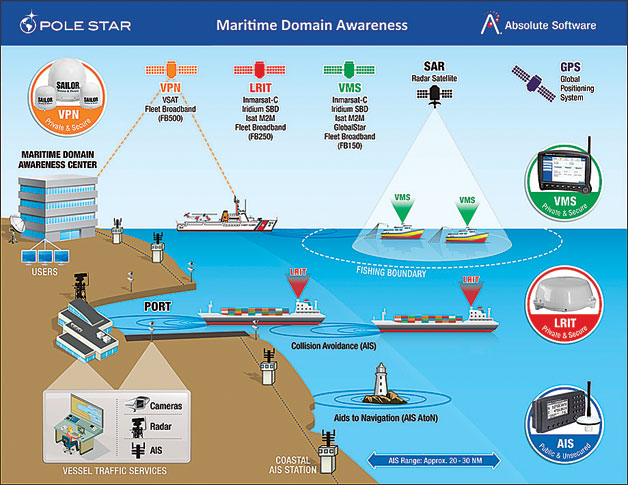

Under the United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2749, the Declaration of Principles Governing the Seabed and Ocean Floor, was adopted by 108 nation states which pronounced that the deep seabed should be preserved for peaceful purposes and is the “Common Heritage of Mankind.” In 1982, the Common Heritage of Mankind concept was stated to relate to “the seabed and ocean floor and subsoil thereof, beyond the limits of national jurisdiction” under Article 136 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea Treaty (UNCLOS). Consequent to decades of deliberations at the international forums the exploration rights of the nations were demarcated and those recognised for India are shown in the box.

Maritime Security Imperatives

Dr Theodore Karasik defines the geo-strategic and geo-economic importance of Indian Ocean as, “despite its significant strategic position as a major trade route and a home to a large part of world population, the Indian Ocean was neglated for a long time. The sudden rise of India and China as global economic powers has significantly increased their energy needs and their dependence on the Gulf oil supplies. Consequently, their energy security interests give these two Asian players direct stakes in the security and stability of Indian Ocean, in particular the safety of transit lines from the Arabian Gulf towards the east coast of the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal which surround India’s long coastal area. This has positioned India and China as major contenders for the share of the Ocean’s dominion.” “The Indian Ocean’s (SLOCs) are also key factors in the global trade and economic stability since the oil and other trading stuff pass through its waterways on the way to Asia, Africa, Europe and other parts of the world. Any disruption in the trade would cause significant stress and strain in many world economies....” This explains geostrategic and geo-economic importance of the region for India and consequentially, huge responsibility to protect and safeguard the nation’s maritime interests behove on the IN.

Since November 2008, several initiatives have been taken by the Government of India to strengthen overall maritime security and the coastal security apparatus against threat of non-state actors from the sea. This entailed seamless integration of all maritime stakeholders, including several State and Central agencies into the new coastal security mechanism. The 15 or more agencies involved, ranging from Indian Navy, Indian Coast Guard, Customs, Intelligence Agencies and Port authorities to the Home and Shipping ministries, State governments and Fisheries departments, etc. To synergise the maritime security efforts of all stakeholders, the IN has established Joint Operations Centres (JOC) located at Mumbai, Visakhapatnam, Kochi and Port Blair. The ultimate aim being establishment of national maritime domain awareness to create an integrated intelligence grid to detect and tackle threats emanating from the sea in real-time and to generate a “common operational picture of activities at sea through an institutionalised mechanism for collecting, fusing and analysing information from technical and other sources like coastal surveillance network radars, space-based automatic identification systems, vessel traffic management systems, fishing vessel registration and fishermen biometric identity databases.

Maritime Security Construct

While the Indian Navy has the single-point overall responsibility for the maritime security which also includes the coastal security, there is a multi-tiered maritime security construct formalised to cover the vast coastlines and the wide expanse of Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). Respective Naval Cs-in-C have been assigned additional responsibility as Cs-in-C, Coastal Defence and head four JOCs. Under a well-defined security mechanism patrolling of the inland waters and riverine contiguous to the creeks and coastlines has been assigned to the State Marine Police of the coastal States and Union Territories, whose jurisdiction extends up to 12 nautical miles (about 22 km). Coastal surveillance and security of areas between 12 and 200 nautical miles (about 22 km to 370 km), which is the EEZ has been assigned to the Indian Coast Guard. IN’s jurisdiction extends beyond 200 nautical miles (370 km). At times this division can get blurred depending upon the operational requirement. The following additional features of maritime and coastal security construct are incrementally being brought into force:

- A National Command, Control, Communication and Intelligence (NC3IN) network would be established for real-time Maritime Domain Awareness linking the operations rooms of the IN and the ICG, both at the field and the apex levels.

- Assets, such as ships, boats, helicopters, aircraft etc. as also the manpower of the ICG being increased.

- A specialised force, “Sagar Prahari Bal” comprising 1,000 personnel and tasked with protecting naval assets and bases on both, the east and the west coasts as well as the Island territories has been created.

- A new CG Regional HQ has been set up in Gujarat, headed by COMCG (North-West), to look after surveillance off the coast of Gujarat, Daman and Diu.

- Vessel and Air Traffic Management Systems being installed by the Ministry of Petroleum, to cover all offshore development areas, as has already been done in the Western offshore region.

- The ICG has been additionally designated as the authority responsible for coastal security within the territorial waters, including areas to be patrolled by the coastal police.

- The DG ICG is designated as the Commander Coastal Command and made responsible for overall coordination between Central and State agencies in all matters relating to coastal security.

- The setting up of nine additional CG Stations to integrate into the ‘hub-and-spoke concept’ with coastal police stations along with manpower.

- The proposal for setting up of Static Coastal Radar Chain and a comprehensive network chain of Automatic Identification System (AIS) stations along the entire coast as well as island territories has been approved.

Maritime & Coastal Security Challenges

The Indian Ocean, especially the Gulf region, witnesses an average daily traffic of some 25,000 bulk carriers, all carrying crude on the high seas. In addition, closer to the coastal region at any given time there are approximately 5,000 fishermen of different nationality engaged in the main trade for their basic survival. It presents a highly sensitive and cluttered security environment.

International boundary lines at sea are wide open and porous. It provides easy access to one and all and does not discriminate based on the intention. Effective measures for border management as on land and within the aerospace cannot be instituted in stricter sense-out at sea. The sea offers very little scope to distinguish between the right of innocent passage or hostile intentions of the vessel transiting through own areas of maritime interests.

Operating in such a dynamic environment the IN has the onerous responsibilities to ensure that lawful private and public activities in the maritime domain are protected against attacks and criminals and otherwise unlawful or hostile exploitations. The surveillance, the constant vigil and the high alert have to be maintained by the Indian Navy 24 x 7.