INDIAN ARMED FORCES CHIEFS ON

OUR RELENTLESS AND FOCUSED PUBLISHING EFFORTS

SP Guide Publications puts forth a well compiled articulation of issues, pursuits and accomplishments of the Indian Army, over the years

I am confident that SP Guide Publications would continue to inform, inspire and influence.

My compliments to SP Guide Publications for informative and credible reportage on contemporary aerospace issues over the past six decades.

50 YEARS / 1971 WAR

Lessons of the 1971 War

A 10-year Integrated Capability Development Plan (ICDP) is in the works that will replace the 15-year Maritime Capability Perspective Plan (MPCC) and focus on a holistic military approach to prioritise inter-service and intra-service procurements and capability building

The Author was the Flag Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Southern Naval Command when he retired on November 30, 2021. He is a Navigation and Direction specialist. His commands at sea include Indian Coast Guard Ship CG 01, IN Ships Vinash, Kora, Tabar and aircraft carrier, INS Viraat. On promotion to the Flag rank he has been the Assistant Chief of Naval Staff (Foreign Cooperation & Intelligence), the Assistant Chief of the Naval Staff (Policy and Plans) at Integrated Headquarters, Ministry of Defence (Navy) and Flag Officer Commanding Western Fleet. On promotion to Vice Admiral he was appointed as the Director General Naval Operations and then the Chief of Personnel, Indian Navy. The Author was the Flag Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Southern Naval Command when he retired on November 30, 2021. He is a Navigation and Direction specialist. His commands at sea include Indian Coast Guard Ship CG 01, IN Ships Vinash, Kora, Tabar and aircraft carrier, INS Viraat. On promotion to the Flag rank he has been the Assistant Chief of Naval Staff (Foreign Cooperation & Intelligence), the Assistant Chief of the Naval Staff (Policy and Plans) at Integrated Headquarters, Ministry of Defence (Navy) and Flag Officer Commanding Western Fleet. On promotion to Vice Admiral he was appointed as the Director General Naval Operations and then the Chief of Personnel, Indian Navy. |

The 50th anniversary of India’s emphatic victory in the 1971 War, and the Indian Navy’s (IN) critical role in the victory, reminds us of many interesting facets of its development and usage in war, and provides us important lessons for the future.

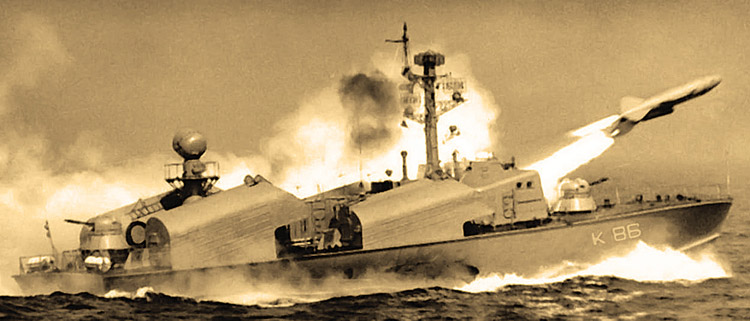

The impetus for the Indian Navy’s success in 1971 stemmed ironically from its non-participation in the 1962 War, as it was confined to our northern borders; and its limited role in the 1965 War, due to political directives of that time. This led the Indian naval leadership of the late 1960s to introspect seriously on the type of role that the Indian Navy could play in the ‘continental wars’ that were likely in the years ahead. The result was the quick acquisition of transformational maritime capabilities from the USSR; the Foxtrot class submarines to finally add the third dimension to the Indian Navy and redress the long standing imbalance with the Pakistan Navy; the Petya class light frigates to fill the gap in capability that existed in anti-submarine warfare; and the OSA I class missile boats from then USSR, which catapulted the IN into the missile age; to name just three. Fortunately, the political leadership of the time understood the urgency of re-arming the Navy and facilitated the acquisitions despite serious national financial constraints that existed during that period. It helped that acquisition procedures then were simple and the weapon systems required were readily available from the Soviet Union at reasonable cost.

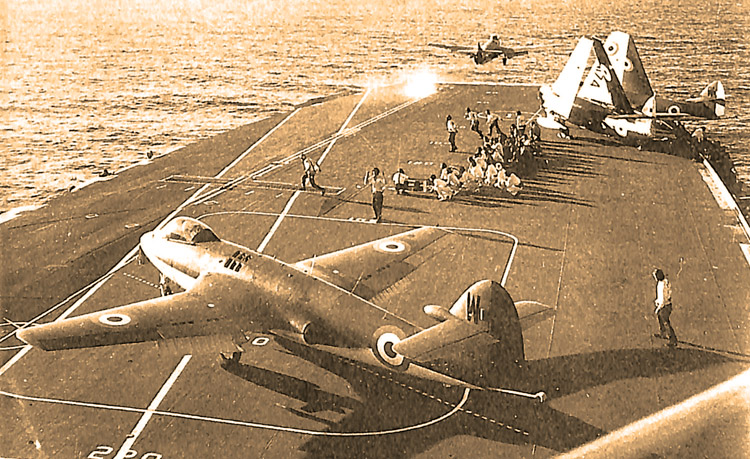

In 1971, the IN comprised just 3,500 officers and about 27,000 sailors. Sparing officers and sailors to go for training abroad and simultaneously set up a full-fledged submarine arm from scratch, as also commission two new classes of ships, besides catering to their administrative, training and logistics support facilities in India, was a difficult task. Yet the Navy persisted and ensured that its new weaponry, along with their trained crew, was ready for operational use by early 1971. The result was that the new weapon systems, combined with carrier-borne air power on Vikrant, and their innovative and excellent tactical usage, enabled the IN to play a decisive role in both theatres of war – the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal.

Political Support

There are many lessons from this period of the IN’s development and deployment at the strategic, operational and tactical levels. At the strategic level, is the lesson for political commitment and support for a Navy’s growth. It is only when the decisionmakers are convinced that investment in building a Navy’s multi-dimensional capability, such as aircraft carriers and submarines, will give them adequate geopolitical returns, will they readily open the nation’s purse strings, as they did in the late 1960s. It is important to note that availability of finances is not a primary consideration, if the leadership is convinced that the investment is genuinely required. As mentioned earlier, the period from 1965-70 was financially not at all sound for India – in fact India had to devalue the Rupee vis- -vis the US Dollar by 57 per cent in 1966 to avert a balance of payments crisis. The period also saw India facing a chronic food shortage, which was deepened by a drought in 1966-67, leading to continued dependence on the US for food imports under the PL-480 provision, which only stopped in 1971. Despite these grim financial circumstances, the fact that funds were spared for naval modernisation, was due to the then naval leadership’s capability to convince the government of the day, as also their sister services, of the necessity of such expenditure. This is no mean achievement, as evident from the prolonged discussion over the acquisition of the Indian Navy’s much needed third aircraft carrier today.

As we pay homage to our ‘greatest generation’ that fought the 1971 War and achieved a spectacular victory of arms – the finest since the Second World War – we would do well to study the campaign again to draw lessons for the future

Operational Capabilities

Secondly, at the operational level, the Indian Navy ensured that it selected the new capabilities with an eye, not only on their ability to inflict substantial damage on its adversary, but also to introduce an unbeatable asymmetry. The acquisition of the OSA I class missile boats in 1971, for example, introduced anti-ship missiles into the Indian sub-continent, and took the Pakistan Navy completely by surprise. Their tactical use too was brilliantly innovative. Envisaged by the Soviet Navy for carrying out swarm attacks against US aircraft carriers and other principal combatants, the Indian Navy used the missile boats against both Pakistani surface combatants and shore targets, which crippled the enemy’s capability, shattered his morale and effectively shut down his only harbour, after which the Pakistan Navy’s surface combatants were effectively hors de combat.

Force Projection

The war in the eastern theatre emphatically underlined the importance of carrier-borne air power for a blue water navy. Vikrant, along with her Petya and Leopard class escort frigates, effectively imposed a blockade against then East Pakistan. Not only did this prevent the reinforcement of the beleaguered Pakistani forces there, it also shut the door on their chances for escape, with the latter dealing a body blow to their morale and playing a key role in Lieutenant General Niazi’s decision to surrender, along with over 93,000 of his officers and men. In addition, Vikrant’s air wing carried out punishing strikes against Chittagong and Cox’s Bazaar harbours, effectively shutting them down for both commercial and military operations. The necessity of carrier-borne air power today, in the face of such capability being invested in by the PLA (Navy), is inescapable. The fact that India has successfully demonstrated its ability to construct aircraft carriers in form of the new avatar of the Vikrant, only makes the argument for a third indigenous aircraft carrier even stronger.

The necessity of carrierborne air power today, in the face of such capability being invested in by the PLA (Navy), is inescapable

Manpower Training

The timely re-arming of the Navy was accompanied by in-depth training of our personnel in the Soviet Union. In the Soviet Navy, training of personnel had the highest priority in peacetime. Their training philosophy of ‘hands on’ skill along with deep theoretical understanding of each equipment, and detailed exploitation documentation, ensured that our personnel could not only deploy the new weapon systems with telling effect, but could also innovate their usage, as seen in the modification of antiship missiles on board the OSA I class missile boats to attack shore targets – in this case the Keamari oil tanks. The necessity for high quality professional training of personnel has become only stronger, as weapon systems become more technically sophisticated and costly to maintain. Consequently, the need to ensure that training continues to be treated as the most important peacetime activity is equally important today.

Leadership

Finally, the high level of morale and motivation among the men who fought the 1971 War made the Indian Armed Forces an unstoppable force. Morale in the military has little connection with creature comforts, perks and privileges. Instead, the morale of a fighting man (or woman) is built on the belief that their equipment is battleworthy and their leaders are professionally competent and willing to put their own lives on the line, when required. In 1971, the high state of morale was due to excellent leadership at all levels, the fact that much of the Navy’s equipment was state-of-the-art, as also the conviction that we were fighting for a just cause. This factor is the most important one for any fighting organisation and should never be overlooked, for even the most sophisticated of equipment is finally manned by an individual, whose will to fight is the intangible factor that will ensure victory, often even in the face of technical or numerical inferiority.

The lessons of 1971 are many and I have only recounted a few of the more important ones here. As we pay homage to our ‘greatest generation’ that fought the 1971 War and achieved a spectacular victory of arms – the finest since the Second World War – we would do well to study the campaign again to draw lessons for the future. While tomorrow’s wars will definitely be different in the manner in which they will be fought, principally due to advances in technology and transformation in the nature and types of warfare since 1971, the lessons discussed above would continue to remain relevant for many years ahead