INDIAN ARMED FORCES CHIEFS ON

OUR RELENTLESS AND FOCUSED PUBLISHING EFFORTS

SP Guide Publications puts forth a well compiled articulation of issues, pursuits and accomplishments of the Indian Army, over the years

I am confident that SP Guide Publications would continue to inform, inspire and influence.

My compliments to SP Guide Publications for informative and credible reportage on contemporary aerospace issues over the past six decades.

Submarine Arm Special

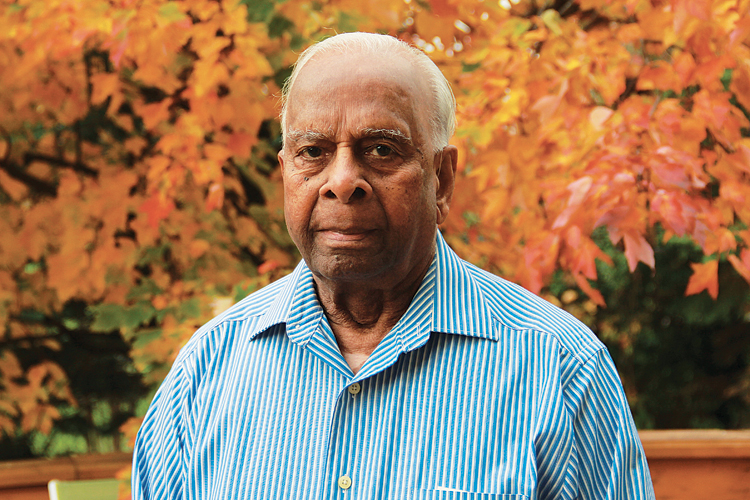

Commodore K.S. Subra-Manian, Commanding Officer of the first Indian submarine, INS Kalvari

“On your efforts will depend the future of the Submarine Arm” —Admiral A.K. Chatterji

In an exclusive interview for SP’s Naval Forces to commemorate the Golden Jubilee of the Submarine Arm of the Indian Navy, Commodore K.S. Subra-Manian, Commanding Officer of the first submarine, Indian Naval Ship Kalvari has reminisced several challenges braved with sheer professional pride by the pioneers of the Submarine Arm of the Indian Navy

SP’s Naval Forces (SP’s): Being the pioneer Commanding Officer of the first Indian naval submarine, would you like to recollect the pangs and challenges in establishing Submarine Arm for the Indian Navy?

Commodore K.S. Subra-Manian (Cmde KSS): I would not call them pangs but certainly there were challenges. We were tasked with something which most of the 16 officers and 104 sailors who formed the first batch had not faced before, having served only in surface ships with little or no exposure to a life underwater. The following signal I received from the Chief of Naval Staff, Vice Admiral A.K. Chatterji on June 20, 1966 emphasised these challenges:

“Personal from CNS for the Officer-in-Charge and all members of the First Submarine Party. With your departure for the USSR the Indian Navy embarks on a new era of growth and expansion. You have a very difficult task ahead but knowing the extremely stringent tests that have been applied to your selection I am confident of your success. I am sure that you will do your best to master the difficult art of submarining and conduct yourselves in the best traditions of the service. On your efforts will depend the future of the Submarine Arm.”

So we were under no illusions about the nature of the challenges before us. Some like myself had some prior experience of submarine life, having trained and served in British submarines for short periods. For the majority, it was their first exposure to submarining. Furthermore, they had to learn about this totally different art in a hostile climate, in a new language and within a mere 16 month training period, including three months learning Russian. In other navies of Britain, USA, Russia and Germany, it took 10-12 years of training and experience to become a Submarine Captain!

SP’s: Would you like to share the memoires of training of surface navy officers and men to convert as submariners for the Indian Navy.

Cmde KSS: Our first task before we actually started submarine training was to ensure that the course of instruction and the syllabi for the various categories of our sailors was suitable and appropriate for us. The organisation and sub-specialisation structures in the Soviet and Indian navies were different. Furthermore, Soviet sailors were mostly conscripts with much less service, doing mandatory service for a short period, unlike our sailors with more than five to six years’ service and some specialisation. Therefore, the pattern and syllabi of training in the Soviet Navy for these conscripts could not be applied to the training of our sailors, and required extensive modification. All this could have been sorted out earlier at a much higher level, but it was left to us even as we commenced training, because there was no submariner at this higher level for advice.

With some difficulty and after considerable discussion, we succeeded in persuading them to agree to get the syllabi modified and thereafter nominated specific sailors for specific training. All these discussions, of course, were going on between attending language classes and looking after the administration and discipline of an Indian Navy shore establishment of 120 personnel — by itself a full time job. In hindsight, I can now say that we made a sound decision to take what was best and suitable for us in the training, organisation, procedures and drills from both our existing model of British origin, and that of the Soviets and to have a new model for ourselves, not an imitation of either. The rest of the Navy, with more acquisitions from Russia, did likewise later on. So now we have our own model — neither Western nor Russian, but Indian.

SP’s: What kind of difficulties and challenges were encountered while inducting and commissioning the first Submarine, INS Kalvari?

Cmde KSS: Before the December date of commissioning, in October 1967 I went from Vladivostok to Moscow, and from there by train with my Engineer and Electrical officers to the White Sea in the north for the deep diving final trial of the Kalvari inside the Arctic Circle. These were completely successful and the submarine easily exceeded her designed maximum depth, inspiring confidence in her capability and robustness of her construction. I encountered no difficulties in commissioning INS Kalvari, except for the fact that after we commissioned her on December 8, 1967, at Balderoi, Riga in Latvia we had to do our workup in the Baltic, in the ice and snow conditions of winter. On the day of commissioning, the temperature was a bracing minus 17 degrees Celsius! Despite the bitter cold, our sailors and officers chose not to wear the shoddy overcoats of coarse material issued to them, as they wished to look smart on this historic occasion, even if it required standing for about two hours in the cold. After the ceremony one young sailor of the honour guard actually fell down unconscious, revived only after an hour with medical attention. Such was the resolve and determination of everyone.

It speaks volumes about the worth, dedication, determination and application of our officers and sailors that they were able to qualify in all the tests and tasks given to them in a completely foreign language in the short time of one year and thereafter operate their submarine not only without any mishap but with confidence and proficiency

As Kalvari was being commissioned into the Indian Navy, we were fully aware that history was being made with the Navy acquiring its third dimension of operation. In addition to operations of ships and naval aircraft on and above the oceans, we now could operate under the ocean and as such had acquired true blue water capability. Signifying this fact, the rank of the CNS was upgraded to full Admiral, at this time and the Eastern and Western Naval Commands came into being under Commanders-in-Chief. My own feelings at this time can best be expressed by quoting from my letter to my wife dated December 7, 1967 — “I write to you on the eve of our great day. Tomorrow morning is the commissioning ceremony when the Soviet flag will be lowered and the Indian flag will be hoisted onboard for the first time in a submarine of our own and I shall read my commissioning warrant ordering me to assume command of our first submarine. I shall pray tonight for God to direct me to perform my duty efficiently and always remain humble, strong and vigilant.”

With the temperature at Riga continuing to drop, and the prospect of the whole harbour freezing over, on December 21, 1967, I took Kalvari about 200 miles south in the Baltic to Baltisk in Lithuania where we continued our workup.

SP’s: What were levels of adaptability of the commissioning crew to operate in totally new technological environment?

Cmde KSS: Earlier I had enumerated the challenges and the problem of language. It speaks volumes about the worth, dedication, determination and application of our officers and sailors that they were able to qualify in all the tests and tasks given to them in a completely foreign language in the short time of one year and thereafter operate their submarine not only without any mishap but with confidence and proficiency. The Indian sailor had convincingly proved his stoic, cheerful and willing capability and versatility in the face of odds and challenges, given trust, opportunity and proper direction.

Aside from this, the sailors of the first submarine contingent made a name for themselves in the city of Vladivostok. The local people had not come across many foreigners, let alone Indians of whom they knew little. They were therefore pleasantly surprised by the courteous and good manners of our sailors who made many friends because of their newly acquired Russian language capability. In the 16 months we were there, I did not have a single disciplinary case involving misbehaviour by any of our sailors. One of our officers who had gone to Vladivostok years later in a submarine for a refit reported that the people there still remembered our sailors of the first party as ‘Kultoorni’, meaning cultured or well mannered.

So now after all these years and having interacted and served with officers and sailors of other countries, I cannot cease to admire and respect such sterling qualities and performance in the true tradition of the Service Most Silent (the Submarine Service). True to this tradition, this performance and level of achievement is unknown and unrecognised by many even in the Navy, let alone the public. Many of them have since faded away to oblivion, unrecognised even as they did not seek anything. It is they who have laid the foundation for the structure of the Submarine Arm as it exists today. If this structure is strong now, it is because of its foundation, and they deserve all credit and appreciation. The message from Admiral Chatterji on June 20, 1966, had said “On your efforts will depend the future of the Submarine Arm”. By their efforts and performance, these officers and sailors ensured that future and fully redeemed the pledge I made in my reply to Admiral Chatterji: “We assure you that we shall strive our utmost to justify your confidence in us”.

SP’s: What were the conditions and degree of challenges during the maiden passage of INS Kalvari from Vladivostok to Visakhapatnam?

Cmde KSS: The year 1968 started ominously for submarines all over the world. The French submarine Minerve and the Israeli Dakar had gone down in the Mediterranean with all hands early in January. Some months later the US nuclear attack submarine Scorpion was lost with all hands in the Atlantic in very deep water.

The maiden passage of Kalvari was not from Vladivostok to Visakhapatnam, but from Riga in the Baltic via the North Sea, the English Channel, North and South Atlantic Oceans and the Indian Ocean.

We sailed from Riga on April 18 and arrived at Visakhapatnam on July 6, 1968, – 79 days to cover about 12,000 miles with goodwill calls en route at Le Havre (France), Casablanca (Morocco), Las Palmas (Canary Islands), Conakry (New Guinea in West Africa) and Port Louis (Mauritius). The leg from Conakry to Port Louis was the longest, being continuous 29 days in most foul weather, particularly while rounding the Cape of Good Hope with mountainous seas submerging the whole submarine even while she was on the surface. Off South West and South Africa the weather conditions were extreme. The officer of the watch and the lone lookout with him had to be lashed to the submarine to prevent being swept overboard and the hatch from inside to the top had to be kept closed to prevent water flooding the submarine. In fact, a 40,000 tonnes tanker ‘World Glory’ broke up and sank not far from us after we had rounded the Cape. No cooking was possible and only dry meals could be provided. When we finally arrived at Port Louis on June 20, most of the submarine’s paint had gone and only the undercoat of red lead paint was left. We were truly Red! As we could not enter a foreign port in this state, the weary crew set to work to paint ship while anchored outside for the first two days with light grey paint, the only colour available even though black was our colour.

Having left India in June 1966 returning in July 1968, the crew had been away from home and their families for over 25 months. The small children they had left behind barely remembered their fathers when they returned! My own son and daughter who were aged three and 1 when I left, did not know me...

With this experience, it can be seen that if the deep diving trial that I attended earlier proved the submarine’s ability to withstand the enormous sea pressure at great depth, her performance in foul weather conditions proved her seaworthiness. Her endurance at sea was also proved as we covered the distance of 12,000 miles without having to refuel even once, and still had reserve fuel left when we reached Visakhapatnam.

SP’s: How did you find the home-coming arrangements for basing the first Submarine; such as shore support, maintenance, essential repairs, product support, etc?

Cmde KSS: On our way from Port Louis to Visakhapatnam, we met IN ships Mysore and Brahmaputra who had come to look at the newest addition to the Navy. I had been informed earlier by Naval Headquarters that there would be no publicity for the historic event of the first Indian submarine entering the first Indian port for the first time, and that at the instance of the Soviets even photographing the submarine would not be allowed. This sounded farcical to us, as anyone could have taken photographs of the submarine when in or near the various foreign ports we had visited and also when shadowed by the South Africans (then under apartheid regime) while rounding the Cape and earlier in the North Sea, the English Channel and the Atlantic by the British, American and NATO countries. So while everyone could have a good look at us, our own people could not!

Having left India in June 1966 returning in July 1968, the crew had been away from home and their families for over 25 months. The small children they had left behind barely remembered their fathers when they returned! My own son and daughter who were aged three and 1 when I left, did not know me when I came back and called me Uncle.

My immediate focus was to plan the well-deserved leave for my ship’s company, ensuring that those who were married went first and then find them places to live. The FOC-in-C, Rear Admiral K.R. Nair in spite of severe constraints of availability of family accommodation, had done whatever possible with what was available. Shore based technical and other support was also needed after the long voyage. Submarines require support from their base when they return to harbour to ease the burden from the crew in need of rest. The diesel engines were due for the mandatory maintenance after the many thousands of hours of operation. To provide such support, a dockyard with necessary equipment and facilities is essential. In our case this was still in the early stages of being set up. There was a Maintenance and Logistics team ashore comprising the naval and civilian technical dockyard personnel trained in the USSR as well as some members of the first contingent. A Submarine Headquarters was therefore set up at Visakhapatnam to coordinate such support, with me in additional charge as the Officer in Charge, SMHQ and being C.O. Kalvari. The sailors of Kalvari who could not be sent on leave also pitched in, foregoing their wellearned break. This was the case for the next few years, till increased base and dockyard support became available.

Two months of rest, reunion and leave and we were back in business. Even though I needed time to evaluate and workup the submarine, and produce all orders pertaining to the submarine such as the Captain’s, Ship’s and Departmental Standing Orders (all of which had to be created from scratch as there were no precedents) and get the crew back in shape after their leave break, this was not to be. As the only submarine in the Indian Navy, we were in demand. From September to November 1968, we were operating with ships of the Western Fleet in the Arabian Sea from Bombay. In 1969 also we were operating in the Arabian Sea while based at Visakhapatnam. In between such exercises, whenever we could, I conducted our own training, as such training needs to be continuous, in a constant endeavour to improve. For the next 18 months, till other newly commissioned submarines arrived and more shore support became available, it was inevitably ceaseless operation for Kalvari, relying mainly on self-help. When setting up any new organisation from scratch, this is unavoidable despite earlier planning.